namespace RTOS {

void init();

void dispatch();

void halt();

void trace();

void error();

void debug_print(const char * fmt, ...);

void debug_led(bool led);

namespace Registers {

extern Event_t triggers;

}

namespace UDF {

void trace(Trace_t * trace);

bool error(Trace_t * trace);

}

}Creating an RTOS (Pt. 2)

Designing and implementing a RTOS based on a Time Triggered Architecture

Author's Note

This blog post is part two in a series originally put together for the University of Victoria's CSC 460 course. The original content was published March 13 2019 by Torrey Randolph and myself. As that webpage no longer exists I am now hosting the content here.

Introduction

The goal of project 2 was to design and implement a real time operating system (RTOS) and a corresponding API to be used in the final project, project 3. The RTOS created for this project is an extension of a time-triggered architecture (TTA) scheduler, with some important new features including support for non-periodic tasks as well as multiple instances of the same task. Many design decisions had to be made including how to represent tasks, what scheduling algorithm to use, and how to keep track of time. These will be described in more detail in the sections below. This report will also cover the strategies used to test our implementation and some hardships we came across during the process.

The only special hardware needed for this project was a single Arduino Mega 2560 board and a Saleae USB logic analyzer. Software dependencies are the same as in project 1, they can be seen listed here.

RTOS

Overview

The simplicity of a TTA lends itself to a simple API, we wanted our RTOS keep this quality. TTA implementations are broken into two phases: a declarative phase, where tasks are defined for the scheduler, and a run phase, or runtime phase, where the scheduler manages the task. What makes our solution truly an RTOS and not just a scheduler is our emphasis on that runtime phase. This will become especially clear when we discuss our much more dynamic conception of tasks when compared to a standard TTA implementation. This focus also influenced our core API and what services we wanted to provide the user beyond simply calling a function at the right time, namely we built the RTOS from the ground up with instrumentation in mind and placed an emphasis on improving the debug experience of lower level C development. The following is a condensed overview of the RTOS API.

The functions init, dispatch, and halt are all essential to the basic operation of the RTOS, taking the responsibility of initializing resources, starting scheduling, and safely shutting down the RTOS respectively. We were selective about what C++ features we wanted to take advantage of for the RTOS, but namespaces were one we decided to capitalize on. Outside of simply helping avoid name collisions, namespaces serve our design to organize more traditional procedural programming constructs into something more familiar to programmers who have seen object oriented interfaces.

The functions trace and error allow both the internals of the RTOS, and user programs to efficiently communicate information with the developer. This could be scheduling information, debug messages, or runtime checks. How these functions works, along with their sister functions in the User Defined Function (UDF) namespace is detailed in the Tracing section of the report.

Outside of these functions, the core functionality of the RTOS involves Tasks.

Tasks

In a standard TTA tasks are defined by an implementation, commonly a function, a period, and an offset. Our RTOS includes these properties and more in order to extend the functionality of a TTA. The comprehensive set of properties are viewable as the fields in the Task_t struct:

struct Task_t {

task_fn_t fn; // A pointer to the task funtion

void * state; // A pointer to the task's associated state

Event_t events; // The events that cause this task to be scheduled

i16 period_ms; // The schedule period of this task (in milliseconds)

i16 delay_ms; // The delay before this task is scheduled

// "hidden" fields

struct {

bool first;

u8 instance; // Used to identify a task during a trace

i64 last; // The last time this task was run

i16 maximum; // The maximum runtime of this task so far

} impl;

};The final three fields of the Task are meant to be used only by the RTOS for bookkeeping. The fields work as follows:

fn: Like in TTA this defines the implementation, a function pointer that will run every time the task is scheduled. These functions are provided their containing Task_t struct as an argument allowing them to self modify and mutate. Additionally, we allow this function to determine whether the Task should be run again by returning a boolean result.state: Providing room in Task_t for the user to store an arbitrary pointer allows for instancing of tasks. This is discussed in more detail later in the report. events: We provide a mechanism for reactive computation by way of event-driven tasks. The events field of Task_t define what events a Task responds to.period_ms: The period is a standard field needed for a periodic TTA. Our RTOS provides accurate scheduling up to one ms. delay_ms: Similar to period, delay is another standard field needed for TTA in order to offset Tasks from one another.first: Some behaviour of Tasks depends on whether it is being run for the first time. For instance a periodic time without delay will be run at time 0. instance: In order to efficiently trace a Task schedule we want to be able to identify a Task by a unique identifier. We reserve one byte to indicate the Task instance. This is not referring to the type of instancing provided by the state field, this instance refers to every instance of Task that exists in the system.last: This field records the last time this Task was run allowing the RTOS to easily calculate its next run time.maximum: This field records the longest time this Task has ever taken to run. For standard periodic tasks this does not impact the Task's execution, but for less essential Tasks this gives the RTOS the ability to make a reasonable guess as to whether a Task can fit into an idle gap.

A key design decision in our RTOS is to represent all types of Tasks with a single construct. A Task is dispatched to the RTOS in two situations. First explicitly, when the user defines the task and then calls Task::dispatch. Second automatically, after a task is run it is reconsidered by the RTOS. This means that a task function can modify its associated Task_t struct in anyway it sees fit, allowing one type of task to become any other type of task. Additionally, tasks can be freely created and destroyed as the RTOS is running, simply by calling the appropriate functions from a task function.

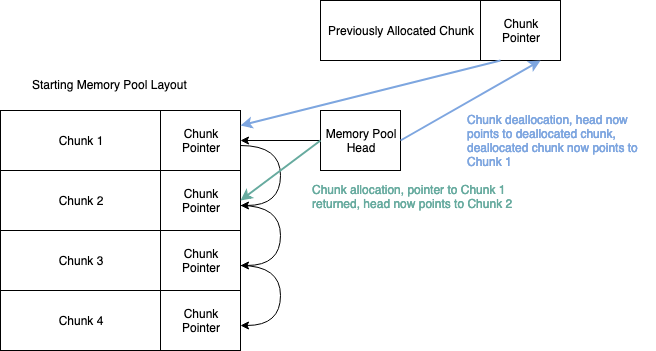

This high level of dynamism means that the RTOS needs to support quick allocation and deallocation of Tasks as well as efficient means of bookkeeping different task types. Rather than depending on the heavyweight solution of malloc and free, we utilize a generic Memory Pool allocator (also sometimes referred to as a refrigerator allocator) to solve both of these problems. Memory Pool allocators can refer to slightly different systems depending on where you look. Our solution focuses on the allocation of like-sized memory chunks. We divide a region of memory into equal size chunks. Each chunk has enough room for the desired object and a pointer to another chunk. By chaining theses chunk pointers together we effectively create a linked list of available chunks. Figure 1 below helps illustrate this setup.

Allocating memory is as simple as popping the head off the list, and deallocating memory is as simple as prepending a chunk back on to the list. This allocation scheme is significantly simpler and faster than more generic allocation schemes, it also has a hidden benefit. When a chunk is allocated its associated chunk pointer is no longer being used by the allocator, this leaves it free to be used to help construct new linked list structures. This is the methodology used by the RTOS for task allocation and management. Tasks are allocated using a Memory Pool, and then organized into linked lists using their associated chunk pointers.

Periodic Tasks

Periodic tasks are time-sensitive tasks that the RTOS aims to always run on time. The are the highest possible priority task. A periodic task is defined by its period and delay. The delay of a periodic task acts as its offset, determining how much time occurs between the task being created and being run. Dynamically created periodic tasks measure their start time from the scheduled time of the task that created them. The scheduled time of a task is the theoretically best time a task would run, not its actual time. This means that if there is a periodic task that dynamically creates another periodic task, that task will still run at the expected time.

The following is an example of creating a periodic task:

using namespace RTOS;

Task_t * my_task = Task::init("my_task", my_task_fn);

my_task->period_ms = 1000;

my_task->delay_ms = 500;

Task::dispatch(my_task);Delayed Tasks

Delayed tasks are another form of time-sensitive tasks. Delayed tasks were added to the TTA to provide a clear method of declaring a "one-shot" task, ie. a task that is run only once. Our implementation of delayed tasks is more flexible however. A delayed task will be run jut once only if no new delay is supplied, or the task function itself returns false. This allows for a delayed task to be run an arbitrary number of times, waiting on a condition for instance, or run with different delays each time.

Delayed tasks are created in the same manner as periodic tasks, only their period_ms field is left at 0.

Event Driven Tasks

Event driven tasks provide a way for our RTOS to respond to urgent events, such as an interrupt occurring. Our RTOS allows interrupts to occur at most times, specifically interrupts can occur during the run time of any task as well as during idle time. This opens up our design to race-conditions. To avoid these painful issues we allow interrupts to only do two things: read arbitrary data and dispatch an event. There is no strict check to ensure that the user does not violate this rule, so it is on them to ensure their program upholds this convention. Event code is carefully written to allow read and writing from interrupts, disabling interrupts at key points in time if necessary.

Events in our system are represented as bits at a specific memory location. The definition for events is provided below:

typedef NUMTYPE_U(RTOS_MAX_EVENTS) Event_t;

namespace Event {

Event_t init(const char * handle);

void dispatch(Event_t e);

}The number of bytes used for events depends on the desired maximum allowed events. We allow for 8, 16, 32, and 64 events corresponding to the different integer sizes. The Event API is limited to two functions, one for creating events and another for dispatching them. Internally the RTOS uses a variable to represent dispatched events. This variable is never read from or written to without first disabling interrupts.

In order for events to be useful tasks need to be able to respond to them. If a task has no delay and no period than it is allowed to become an event-driven task. A task sets its event field with the bits corresponding to the events it wants to listen to. When that even fires it will be scheduled in the next available idle gap, so long as no delayed task is waiting to run.

Each event can only drive a single task, but a task can listen to multiple events. When an event-driven task is run a the RTOS::Registers::triggered variable stores what tasks triggered the task to run. After running the event is considered cleared and will not trigger the task again until the event is dispatched again.

The following is an example of creating an event-driven task that listens for two different events:

using namespace RTOS;

Event_t event_1 = Event::init("event_1");

Event_t event_2 = Event::init("event_2");

Task_t * my_task = Task::init("my_task", my_task_fn);

my_task->events = event_1 | event_2;

Task::dispatch(my_task);Keeping State

In a normal TTA, each run of a task is a new activation of that task; tasks have no way to keep track of their history, or their state. This also means that two tasks with the same task function will have the same effect. By providing a pointer for state on Task_t we allow tasks to maintain state and have a notion of different instances.

Keeping Time

Time is an important part of a real time operating system. The operating system has to have a concept of time, however that is implemented. Our RTOS uses a hardware timer set to interrupt every millisecond to keep track of the current time. This timer increments a global variable representing the time in milliseconds since the RTOS was dispatched. Two factors had to be considered while developing this system: the precision of the timer and the size of our variable.

The crystal oscillator on the ATMega2560 runs at 16 MHz. Hardware timers can be configured to use the CPU clock directly or to use a scaled version of that clock. We configured Timer/Counter 1 on the ATMega2560 to use a clock with one-64th the frequency of the CPU clock. This, along with its interrupt set to trigger when the counter reached 250, produced a timer interrupt that went off every one millisecond. One millisecond precision was found to be enough for our system, providing us decent precision while limiting the CPU time spent updating our global time variable.

When deciding what size of variable to use, we calculated how long various sizes would take to overflow. Only signed integers were considered because the time is used in many arithmetic computations. With a 32-bit field, the largest number that can be represented is 2,147,483,647. That equates to 24 days of time-keeping before our variable would overflow. While that would be sufficient for the purposes of this project, we decided to instead use a signed 64-bit field, giving us roughly 292 years of time-keeping ability.

Scheduling

The RTOS scheduling procedure is where we achieve most of the desired functionality. The following is the source code for thee RTOS inner loop:

void dispatch() {

Time::init();

MAIN_LOOP: for (;;) {

i64 this_time = Time::now();

i64 idle_time = 0xFFFF;

Task_t * task;

task = Registers::periodic_tasks;

if (task != nullptr) {

i64 time_remaining = Task::time_remaining(task, this_time);

if (time_remaining <= 0) {

// We need to pop the task off the list before running the task

// Run will handle re-inserting it correctly

Registers::periodic_tasks = Task::cdr(task);

Task::run(task);

goto MAIN_LOOP;

} else {

idle_time = min(idle_time, time_remaining);

}

}

task = Registers::delayed_tasks;

if (task != nullptr) {

i64 time_remaining = Task::time_remaining(task, this_time);

if (time_remaining <= 0) {

if (Task::fits(task, idle_time)) {

// We need to pop the task off the list before running

// the task. Run will handle re-inserting it correctly

Registers::delayed_tasks = Task::cdr(task);

Task::run(task);

}

goto MAIN_LOOP;

} else {

idle_time = min(idle_time, time_remaining);

}

}

task = Registers::event_tasks;

if (Registers::events) {

while (task != nullptr) {

if (task->events & Registers::events) {

if (Task::fits(task, idle_time)) {

Task::run(task);

}

goto MAIN_LOOP;

}

task = Task::cdr(task);

}

}

Time::idle(this_time, idle_time);

}

}The scheduling procedure is broken into four key steps. Scheduling periodic tasks, scheduling delayed tasks, scheduling event tasks, and idling. By maintaining our periodic and delayed tasks in sorted order, where the first task in the list is the next to run, we only have to check if the first task in each of these lists is ready to run. Task have a Task::time_remaining function which roughly return:

This means that a task is ready to run when its time remaining is equal to zero. We compare using less than or equal to for the case of a missed task. In reality this function is slightly more complex as periodic time begins at zero, and the notion of time remaining is not sensible for event-driven tasks.

If any task is successfully scheduled, or a task fails to fit within the remaining idle time, we immediately return to the start of the loop to ensure that our priority order is properly maintained. A task can fit if its maximum time is less than the current idle time. When first running a task our RTOS is naively optimistic, assuming the task will take zero milliseconds, but each run the maximum time is updated, and if that task does not fit in the idle time it will be skipped.

When periodic or delayed tasks are run, they are removed from their respective lists, moving the next to run task to the top. They will be reinserted in sorted order by Task::run if necessary. The same goes for adding event tasks that dynamically change to and from other task types. Note that because event tasks are prioritized first come first serve, we have to iterate over the entire event list in order to check if one needs to be scheduled.

If no task can currently run we idle until the next time sensitive task is ready to run. This is done using the following function:

void idle_mode() {

set_sleep_mode(SLEEP_MODE_IDLE);

sleep_mode();

}

void idle(i64 this_time, i64 idle_time) {

// Get most accurate idle time

i64 now_time = now();

idle_time -= (now_time - this_time);

// Check if time has already passed by now

if (idle_time < 1) {

return;

}

// Delay

while(now() - now_time < idle_time && !Registers::events) {

idle_mode();

}

}During idle time we put the CPU into Idle Mode using the appropriate AVR Libc functions. This helps reduce power consumption. Because we keep time using an interrupt, we are guaranteed to idle for no more than one millisecond at a time. When we wake up we check whether the appropriate amount of time has passed or if an event has gone off, in which case we return to the scheduler.

If a task misses its scheduled time, an error is traced, however the task will maintain the schedule it would have had should it not have been missed. For instance if a task is expected to run every 1000 ms, runs for the first time at 2000 ms, but misses its second run, running instead at 3001 ms, it will still be scheduled for 4000 ms, not 4001 ms. This makes the RTOS scheduling much easier to predict even when some tasks experience slight jitter.

Tracing

Tracing occurs throughout the RTOS. Anytime a Task is created, started, or stopped, memory is allocated, the CPU is put into idle mode, all of these actions and more are traced. Tracing is done by updating a trace struct with appropriate values and then issuing a call to trace. This will call the UDF of the same name. It is up to the user programmer to decide what to do with tracing information. Additionally, we allow the user programmer to opt out of tracing using preprocessor directives allowing the RTOS to run without the overhead of tracing. The actions captured by tracing are best summarized by looking at the tagged union used to represent the data:

enum Trace_Tag_t {

// Definitions

Def_Task, // The creation of a task

Def_Event, // The definition of an event

Def_Alloc, // The allocation of memory

// Marks

Mark_Init, // The start of the RTOS

Mark_Halt, // RTOS exucution is about to stop

Mark_Start, // The start of a task

Mark_Stop, // The end of a task

Mark_Event, // The occurence of an event

Mark_Idle, // Scheduled idle time

Mark_Wake, // Woke up from idle time

// Errors

Error_Max_Event, // Maximum number of events exceeded

Error_Undefined_Event, // Undefined event dispatched

Error_Max_Alloc, // Maximum memory allocation exceeded

Error_Max_Pool, // Maximum pool allocation exceeded

Error_Null_Pool, // Null pool or chunk pointer passed as argument

Error_Max_Task, // Maximum tasks exceeded

Error_Null_Task, // Null task passed as argument

Error_Invalid_Task, // Invalid task configuration provided

Error_Duplicate_Event, // Two tasks act on the same event

Error_Missed, // A task schedule was missed

// Debug

Debug_Message, // Used to send messages to the tracer

};

typedef struct Trace_t Trace_t;

struct Trace_t {

Trace_Tag_t tag; // The trace tag

union {

union {

struct { const char * handle; };

struct { const char * handle; u8 instance; } task;

struct { const char * handle; Event_t event; } event;

struct { const char * handle; u16 bytes; } alloc;

} def;

union {

struct { u64 time; };

struct { u64 time; u16 heap; } init;

struct { u64 time; } halt;

struct { u64 time; u8 instance; } start;

struct { u64 time; u8 instance; } stop;

struct { u64 time; Event_t event; } event;

struct { u64 time; } idle;

struct { u64 time; } wake;

} mark;

union {

struct { Event_t event; } undefined_event;

struct { Event_t event; } duplicate_event;

struct { u8 instance; } invalid_task;

struct { u8 instance; } missed;

} error;

union {

struct { const char * message; };

} debug;

};

};The Trace tags vary in purpose from scheduling information to runtime error checking. Definition traces, for when a user programmer defines a Task, Event, or allocates memory also provides a human readable handle which can be useful for visualizing trace results. We use a tagged union to try and minimize the overall memory footprint of Traces. The precise size of a Trace will vary between 12 and 18 bytes depending on the specified number of Events the user needs.

Error traces are provided to the user programmer even when normal tracing is disabled. These correspond to various unexpected events, such as running out of memory, or a task missing its scheduled time. It is up to the user program to decide how to react to these errors. The UDF error function is passed these traces, if it returns true the RTOS will continue execution, otherwise it will halt immediately. This allows programs to react in different ways to different error states. For instance some programs may wish to crash if a specific task is missed, but not crash for others. This system allows for that level of fine grained control.

The RTOS provides two built in methods of handling traces, pin tracing and serial tracing. With pin tracing the function Trace::configure_pin can be used to assign digital pins to specific tasks. If the UDF provides all traces to Trace::pin_trace, the RTOS will automatically set the appropriate digital pins high and low as tasks run. This makes integration with a logic analyzer trivial.

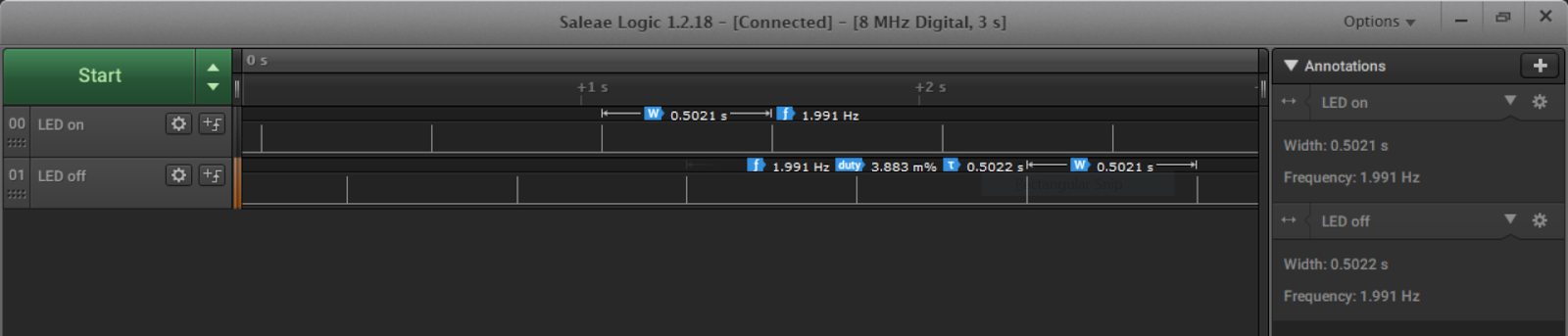

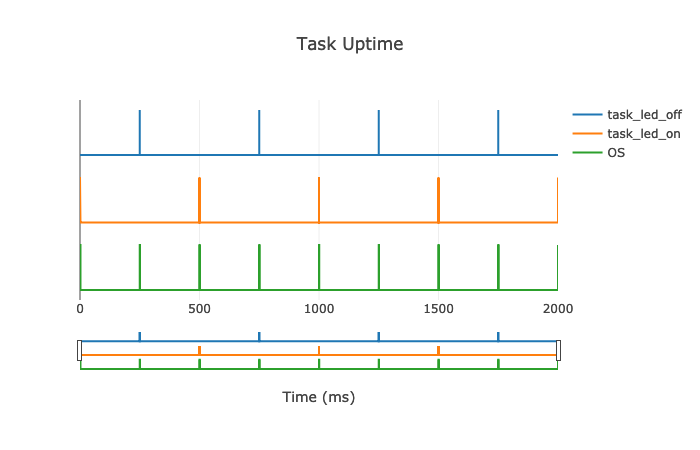

Serial tracing will output the trace bytes directly to a serial port. We wrote a small python module that could decode the trace and keep a log. This module would print the trace in a JSON format to stdout as well as print RTOS debug messages to stderr. We combined this functionality with a small web server that served these logs and a small webpage for visualizing the results. To provide an idea of how this works, here is the logic analyzer results for one of our tests, compared to the visualized results from our python module:

In addition to plotting the trace of tasks we also used the webpage to display additional information, such as RTOS memory usage, and general statistics about CPU utilization and task times. This interface provides a sort of real time dashboard for the board, as the webpage can be updated as the board runs and traces arrive on the serial port. This became an indispensable tool during development.

Testing

Overview

Time-sensitive applications are notoriously hard to test, let alone the RTOS running underneath them. However, to ensure that everything is working properly, testing is necessary. One popular way to test real-time systems is by having the system produce a trace of what is going on so that the user can visually analyze the results. To make sure the system behaves correctly and will not produce unintended results, developers try to force the system to exhibit bad behaviour. If the system has been implemented correctly, it will deal with these situations as predicted and produce an expected trace.

Time-insensitive features or components of a software program can be tested without producing a trace and instead by writing unit tests. The unit tests described below used software assertions to verify expected behaviour of each component.

For any time-sensitive features, schedule tests were created to use traces produced by our RTOS to verify correct behaviour. These tests can be set up to use any of the tracing methods described above as a verification method, as well as additional software assertions. The twenty-one schedule test cases below were ran multiple times during development to ensure systems were not broken in the process and that everything worked as expected after code was finalized.

Unit Tests

Event Tasks

Tests a number of functions involving events. Creates and asserts the uniqueness of events, tests dispatching them and ensuring and global variables for the RTOS are updated correctly. Tests that all of these actions produce correct traces. Also tests that error traces will occur if too many events are created, or an undefined event is dispatched.

Memory Tests

Tests the static and pool allocators provided by the RTOS. The static allocator simply provides one time dynamic memory allocation without any ability to free memory. Pool allocators are tested to see if they provide usable, safe memory, and can be combined into lists and deallocated. All of these steps are checked for correct traces, and in the case of either the static allocator or pool allocator running out of memory, an error trace is expected.

Task Tests

Tests the creation of tasks, and ensues that RTOS global variables are updated correctly when tasks are dispatched. For instance periodic tasks are dispatched and their order is checked to ensure that the RTOS correctly sorts them. Event tasks are also tested to ensure that they appear in FIFO order and will create an error trace when two tasks attempt to listen to the same event.

Scheduling Tests

01 - Single Periodic Task

Tests that a periodic task runs repeatedly and on time.

02 - Multiple Periodic Tasks

Tests that two alternating periodic tasks run in the correct order and at the correct times.

03 - Single Periodic Task with Offset

Tests that a periodic task with an initial delay runs at the correct times. For example, a task with a period of 500 milliseconds and an initial delay of 200 milliseconds should run at the following times: 200 ms, 700 ms, 1200 ms, 1700 ms, etc.

04 - Overlapping Periodic Tasks

Tests that two periodic tasks scheduled to overlap each other will cause the second task to miss its deadline and an Error_Missed error to be sent to the user.

05 - Defining Tasks in the Wrong Order

Tests that the scheduler schedules tasks in the correct order regardless of the order they were dispatched in. Two periodic tasks were created, each with a period of 500 milliseconds. One of the tasks, Task 2, also had an initial delay of 250 milliseconds. Though Task 2 was dispatched to the operating system before Task 1, the scheduler correctly ran Task 1 before Task 2.

06 - Instances of a Single Task

Tests that two instances of a single task retain their separate states correctly. Two periodic tasks were created; Task 1's state field was assigned the value of true and Task 2's was assigned the value of false. Every time the task function was ran, depending on the instance of the task currently being executed, it asserted that the state field was true or false as expected. This demonstrated that two tasks sharing the same task function have separate states.

07 - Event Occurring Prior to OS Dispatch

Tests that the operating system is able to remember events that may occur between the time that the operating system is initialized and dispatched.

08 - Terminating Delayed Task

Tests that a single delayed task is run once at the correct time and then never run again.

09 - Terminating Immediate Task

Tests that a single immediate task (a delayed task with delay_ms of zero) is ran once and then never run again.

10 - Repeating Delayed Task

Tests that a single delayed task that creates itself is put back in the queue and ran again at the correct time.

11 - Interrupt During Periodic Task

Tests that a periodic task is allowed to finish execution after an interrupt goes off in the middle of it. The corresponding event-driven task is run after the periodic task completes. Furthermore, the periodic task is run at its next scheduled period.

12 - Interrupt During Delayed Task

Tests that a delayed task is allowed to finish execution after an interrupt goes off in the middle of it. The corresponding event-driven task is run after the delayed task completes.

13 - A Long Task in a Short Idle Time

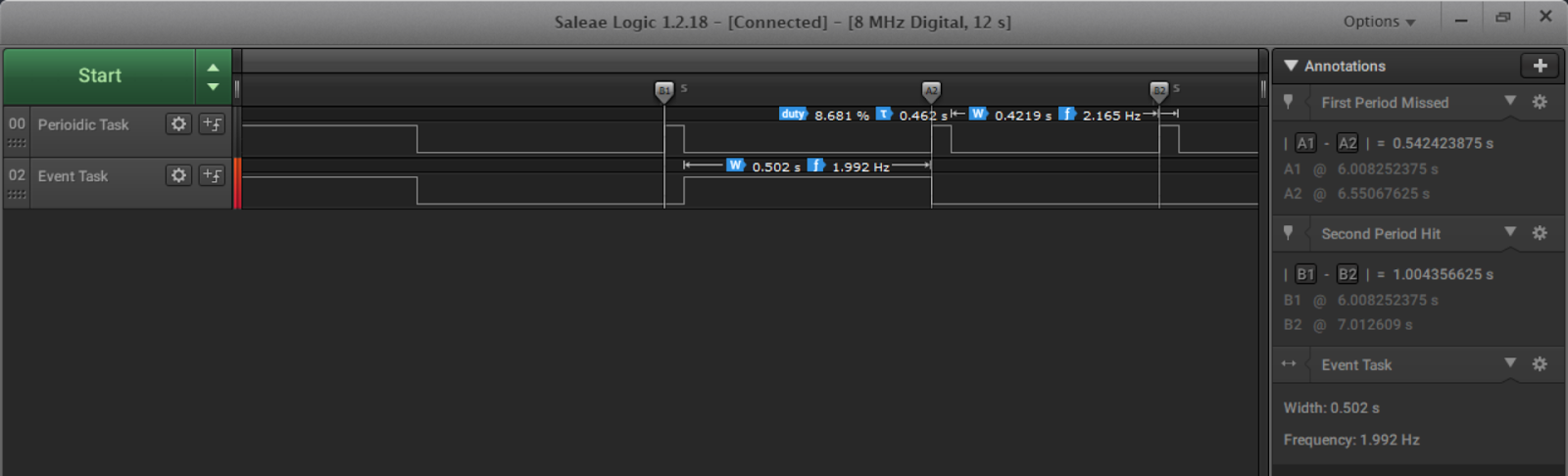

Tests the scheduler's ability to determine if a task will fit in a given idle time. In this test, a periodic task was created and schedule to run for 40 milliseconds every 500 milliseconds. An event-driven task was created and set to run for 500 milliseconds when triggered. Below, Figure 2 shows the correct sequence of events that occurred. At timing marker A1 the periodic task executed for 40 milliseconds. During that time, a timer interrupt went off, triggering the event. The periodic task completed its execution and then event-driven task ran for 500 milliseconds. When the event-driven task completed, the time was roughly 540. Though the periodic task was supposed to run at time 500, it missed its deadline due to the length of the event-driven task. The operating system will have noted the running time of the event-driven task and at the start of the next idle time, even though the event is triggered again, the scheduler correctly determines that it does not have time to run the event-driven task.

14 - Multiple Interrupts in a Long Idle Time

Tests that an event-driven task runs multiple times during a single idle period if the event is triggered multiple times and the task fits within the time constraint.

15 - Periodic Task Becoming Delayed

Tests that a periodic task can dynamically become a delayed task. A periodic task may set its period_ms field to zero and its delay_ms field to non-zero to transform from a periodic task to a delayed task.

16 - Delayed Task Becoming Periodic

Tests that a delayed task can dynamically become a periodic task. A delayed task may set its period_ms field to non-zero to transform from a delayed task to ta periodic task.

17 - Periodic Task Becoming Event-Driven

Tests that a periodic task can dynamically become an event-driven task. A periodic task may set its period_ms field to zero and its events field to the desired event(s) to transform from a periodic task to an event-driven task.

18 - Event-Driven Task Becoming Delayed

Tests that an event-driven task can dynamically become a delayed task. An event-driven task may set its events field to zero and its delay_ms field to non-zero to transform from an event-driven task to a delayed task.

19 - Delayed Task Becoming Event-Driven

Tests that a delayed task can dynamically become an event-driven task. A delayed task may set its events field to the desired event(s) to transform from a delayed task to an event-driven task.

20 - Event-Driven Task Becoming Periodic

Tests that an event-driven task can dynamically become a periodic task. An event-driven task may set its events field to zero and its period_ms field to non-zero to transform from an event-driven task to a periodic task.

21 - Unchanged State When Changing Task Type

Tests that a task's state field is retained when changing between task types. If a task dynamically changes its type, its state field should remain unaffected.

Obstacles

No software program is written bug-free on the first go around and ours was certainly not an exception. Thanks to our tracing systems and our test suites, we were able to find and resolve multiple bugs in our system. These ranged from simple mistake such as breaking out of a nested loop with continue rather than a goto statement to more serious bugs, such as creating infinite loops. Our implementation of the linked lists which held Task structures could, in some cases, produce cyclical lists that resulted in infinite loops and task not being terminated correctly. Along the same lines, one major bug we found was that a task that dynamically changed to an event-driven task type would never get put into the event-driven task list. This was a result of a missing condition in an if statement in our scheduler. Thankfully, we tested this case and found this bug.

Another interesting flaw we caught was relating to how we calculated the time remaining until a given task wanted to run next. Our initial calculation did not allow periodic tasks to run at time zero and, instead, calculated their first time remaining to be the length of their period plus their delay. To fix this, we added the first field to the Task_t structure to mark the first running of each task and set our scheduler to perform a slightly different calculation of time remaining on their first run.

Along with multiple implementation-specific bugs, there were a couple typical pitfalls that we came across while implementing our real time operating system. Thankfully, they were realized before major bugs were caused. These pitfalls included forgetting to declare certain variables as volatile, and forgetting to disable interrupts during certain critical sections. Both of these are common errors made in development of time-sensitive systems.